Every CEO, it seems, has to be made to look like a dashing Confederate cavalry general or a boardroom Elvis Presley.Peter Drucker

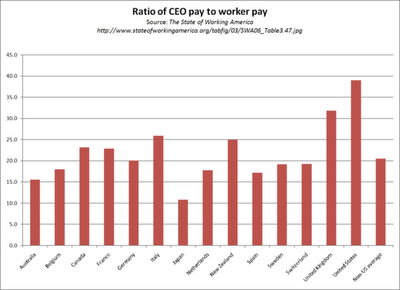

But leaders require much more ordinary, solid qualities, such as showing respect for employees and their work. Drucker thought nothing destroyed leadership as effectively as excessive CEO compensation. Inequality foments disillusionment among lower level management and the company's wage earners, corroding mutual trust between the enterprise and society. Yet CEO pay has soared since WWII, and partly it is due to the compensation systems the have chosen which favor themselves while seeming objective—peer group benchmarking!

The unnecessary use of external peer group benchmarks to set management compensation is causing executive pay in the United States to rise inexorably without merit. Peer group benchmarking—now so widely utilized that it is enshrined in federal regulations—has become the corporate standard even though it was never intended to determine senior management compensation and was not designed to do so. Initially used after World War II to compare jobs like, say, accountants and civil engineers across companies, peer group benchmarking of salaries was an easy but misguided approach that eventually was used for CEOs and senior executives. Corporate boards need to cut their emphasize on peer grouping, and increase their emphasis on the company and its executives' accomplishments in setting their pay.

A report by the IRRC finds corporations should move away from formulaic peer group analyses in judging compensation packages, and hold directors accountable for their judgements. Companies are better served when directors use discretion—down as well as up—in setting compensation levels. Shifting to a compensation system that focuses on internal, company specific and success related methods will help solve the problem of excessive compensation plaguing many public corporations, resulting in a more reasoned compensation approach, improved board oversight, and a healthier corporation.

- Peer group theories are misguided because they are based on the idea of responsive, competitive markets for executive talent, though executives are not constantly changing their company loyalties.

- Systemically, a formulaic reliance on peer grouping will lead to spiraling executive compensation, even if peer groups are well constructed and comparable.

- Even boards made up of faithful guardians of shareholder interests will fail to reach the levels of compensation merited when they rely on the faulty and costly process of peer benchmarking.

- Boards should measure performance and determine compensation by focusing on factors directly important to the company.

In summary, the solution is to avoid arbitrary application of peer group data to set executive compensation levels. Instead, compensation committees must develop internal pay standards based on the specific company, its competitive environment and its dynamics. If customer satisfaction is deemed important to the company, then results of customer surveys should play into the compensation equation. Other such factors include revenue growth, cash flow, and other measures of return, an executive's current and historic performance and internal pay equity. Some reference to peer groups may be warranted, but the compensation process must maintain the flexibility necessary to retain and encourage talent in the managerial skills particularly important to that company, skills that should be continually assessed.

Authors of the report, Executive Superstars, Peer Groups and Over-Compensation—Cause, Effect and Solution, were Charles M Elson, Edgar S Woolard, Jr, Chair and director of the John L Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware, and Craig K Ferrere, the Edgar S Woolard Fellow in Corporate Governance at the Weinberg Center. Download the full IRRC report.